When we think of famous artists, not many of them will be Muslim, but that’s not to say it isn’t a part of our heritage. In fact, Islam is all about that expressive life – just not through portraits perhaps. However, it’s important to note that whilst other religions and their arts are rooted in faith, “Islamic Art” isn’t a term as such, because the religion itself is not depicted. It’s simply something that blossomed from the culture in the lands where Muslims ruled. So, what is there for us to reclaim from our golden history that gels so well with mental health?

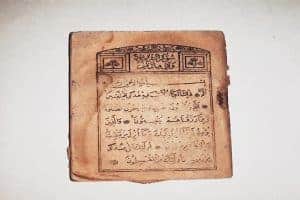

Let’s start with the source of Islam, the Quran. Many scholars and teachers of today will often reference Arabic (in particular Quranic Arabic) as beautiful and point out the patterns that occur. Muslims in history utilised this repetition, these patterns and the depth of the definition of words to create ground-breaking poems with elaborate structures to them for the purpose of memorising and understanding the religion further. One of the most famous poems with almost 700 lines long was written by Abu Muhammad Al-Andalusi Al-Qahtani titled Nunniyah Al Qahtani – which is an integral part of many Islamic schools worldwide. It was given its name because of the repetition of the letter ن (“noon” in Arabic). The poem covers religious understanding, as well as social struggles and how to stay united. However, in many narrations from the Sahaba they may refer to “Arab poets” who spoke about death, heartbreak, family etc so poetry has always been a part of our tradition and a way to provoke thoughts. It’s also refreshing to see that it has now evolved to fit into our norms such as many young Muslim spoken word and nasheed artists!

Intellectual thinkers also went beyond the face value of the Quran and derived many art forms to study such as the different types of tafseer e.g. thematic tafseer, tafseer that connects the miracles embedded in the Quran, tafseer that focuses on words themselves, the location of particular passages and of course the mathematics within the scripture.

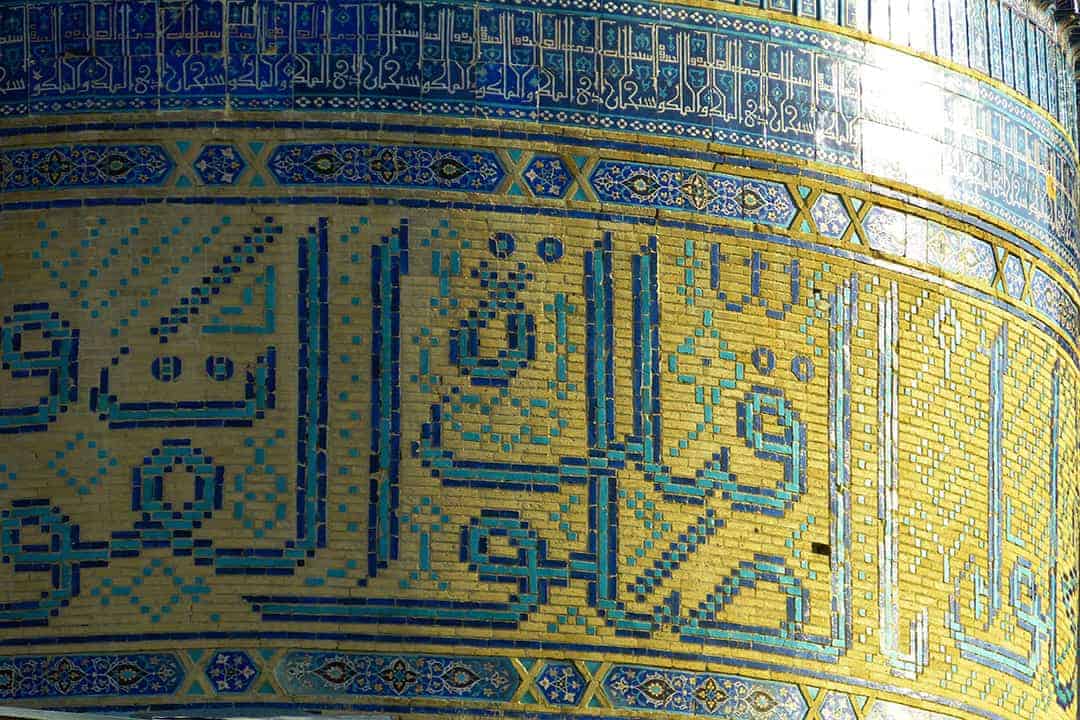

Let’s zoom out a little. Open your Quran, what do you see? As a child, were you ever told off for tracing the intricate floral geometric borders with your fingers instead of actually memorising your surah? Geometric designs, besides calligraphy and vegetal patterns are probably the most iconic types of design that are attributed to Muslims, and of course we should take pride in this, it’s breathtaking! (Almost kind of soothing to look at too, do you agree?)

These extravagant-yet-simple designs adorn our mosques, our books, our clothes and even our cutlery. Whilst we’re sure they must originate from all over the world, they are thought to have flourished from Iran, Turkey and China and as the Muslim Empire grew, different cultures adapted it to their own style and taste. While of course it may have been a hobby, and unlike nowadays you can create and copy these patterns repetitively on particular software; in those days they would have to sit for hours, pay attention to the tiniest of details and create symmetrical realms of colour and depth. Almost as if it is a small attempt to match the depth of Islam.

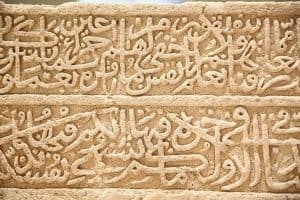

Moving swiftly on to calligraphy, a distinctive element to Islam with many artists using their skills for gifts, or decorative reasons; often making use of Arabic and making it pleasing to the eye. With the sheer amount of variations as there are different types of lettering scripts, it highlights the individual differences of Muslims all around the world.

It’s all well and good when we go on about the wonders that art can do for your mental health, but what does it actually do?

Last week we mentioned a few factors about it changing cognitive processes and takes up room for more positive thinking than wasting energy on snowballing, however there are more studies than ever before, finding out the great effects of what a small amount of “letting go” can do for you. Cortisol (stress hormone) is reduced greatly within just 5 minutes of doing an art form, and, by the way, this doesn’t depend on how much art experience you have or your skill level. People even described it as helping them put things into “perspective” and allowing them to be “absorbed” into their activity without letting their “mind run wild with obsessive and negative thoughts” (Kaimal 2014). Other reports have suggested that “engaging in creative behaviour leads to increases in well-being the next day, and this increased well-being is likely to facilitate creative activity on the same day” (Ough 2016).

If you are looking for a few ideas on how to creatively cope, check out Hafsah’s10 ways to do #creativecoping and for more inspiration check out our social media for #creativecoping this month. In the meantime, keep reading and carry on being creative!