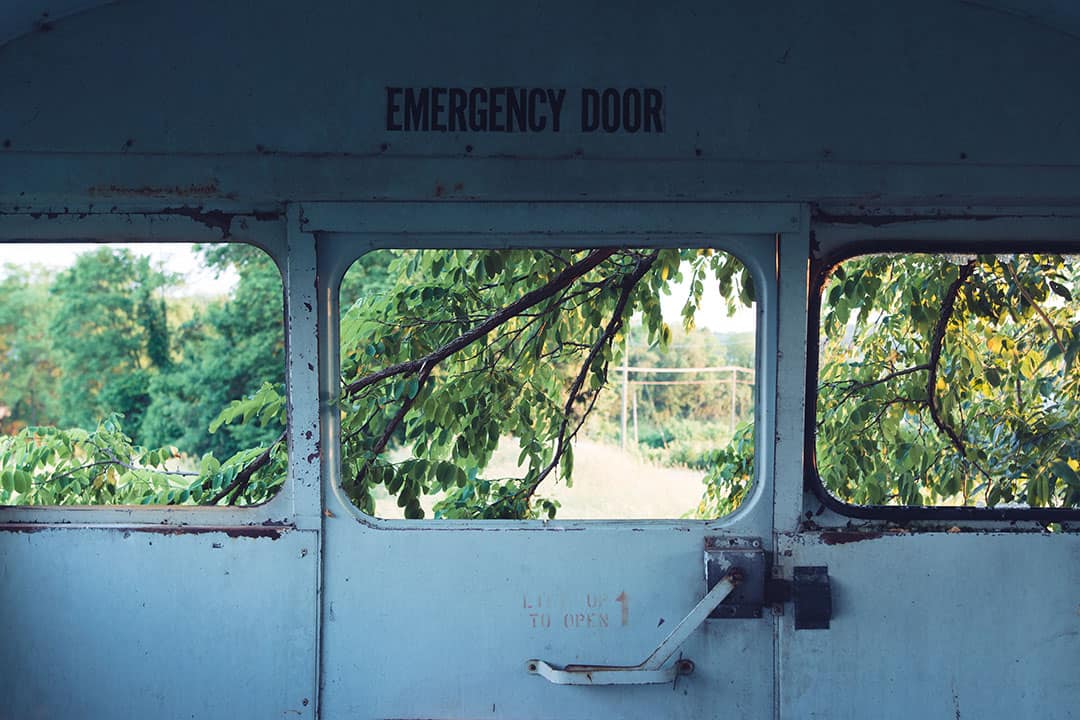

The vulnerable situation of a war victim.

“Someone or something that has been hurt, damaged, or killed or has suffered, either because of the actions of someone or something else, or because of illness or chance.”

The dictionary definition of victim above doesn’t capture the full scope of the word or the stigma and certain prejudices faced for being one. With being a war victim also comes the labels of ‘refugee’ or ‘asylum seeker’ and the repercussions of war, things that continue to affect in day to day living especially since modern wars – where the distinction between fighters and civilians are blurred and even deliberately disregarded – often demand the sacrifice and suffering of the whole population.

When it comes to war, there’s no doubt that there are victims, many will have faced oppression and torture of some form in their country of origin – according to the IRRC the notion of ‘war victims’ has several connotations: from its narrow sense in international law – where it denotes a person who has been harmed by the consequences of an internationally unlawful act – to its broader sense where it refers to all persons whom humanitarian law seeks to protect in armed conflict.

Sadly, arrival into a country does not in itself bring peace of mind, since dealing with difficult procedures, attending to basic welfare, adjusting to a different culture and language has to be dealt with, all whilst being in a state of limbo not knowing whether they will be forced to leave again. It isn’t all hunky dory for people to have fled a country and end up in another, the media tend to focus on the economic ‘problems’ rather than the refugees’ issues, which in turn marginalises all their experiences – everyone has their own story to tell. The reality of being a refugee, with the consequent mental traumas that have led someone to seek possible sanctuary abroad, is often ignored or minimised. We have to understand that being an asylum seeker/refugee is a major event in someone’s life but it doesn’t mean it is their whole story.

Research has found that asylum seekers and refugees are more likely to experience poor mental health, even fives time more likely than the general population with more than 61% experiencing serious mental distress (Eaton, Ward, Womack & Taylor, 2011), including higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other anxiety disorders (Tempany, 2005).

They face complex challenges related to their mental health and are often at a greater risk of developing mental health problems; understandably, this is due to many factors such as an upheaval of a sense of security, identity and losing loved ones.

The increased vulnerability to mental health problems is linked to pre-migration experiences (e.g. war trauma) and post-migration conditions e.g. separation from loved ones, difficulties with asylum procedures and poor housing to name but a few (Steel et al, 2009). Let’s not forget that the actual migration experiences regardless of it being a child or adult can be mentally, physically and emotionally burdensome.

At a time of austerity and cuts to services, the most isolated in our communities, including vulnerable victims of war can feel ignored and not supported. Support is needed in assisting rebuilding of lives, so that they may prosper not just in financial and health terms, but in terms of opportunities given. Additionally as a community we can do better and more to help their plight (rather than just throwing money at them) by interacting and empathising with them as well as raising awareness that more mental health commissioning for the refugee/asylum seeker population is needed.

We pray that those victimised find strength, hope and ease in reconstructing their lives again Ameen.